An Interview-ish Interview

"Making Things" Authors Erin Boyle and Rose Pearlman talk to each other about things, broadly, and the making of them, more specifically.

Risking redundancy, I’ll say: I really like making things. I even ran a magazine about making things with fiber for 6 years. And here, in this new-ish context, we sure do make a lot of things.

In between the magazine and the here/now, I ran a little shop selling vintage kids clothing—the general flow of stuff having to do with kids and the waste therein motivating that particular idea.

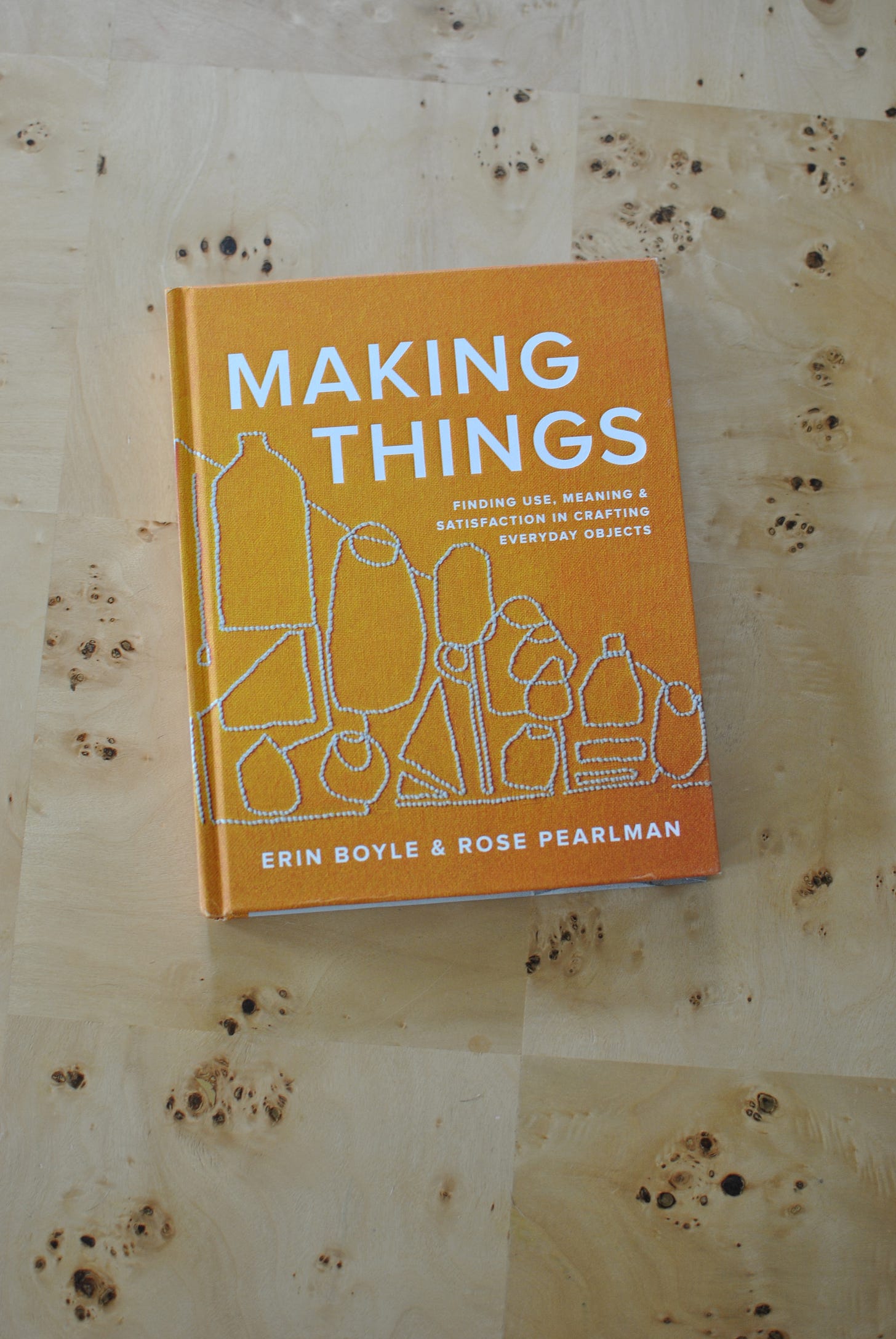

So, it should come as little surprise, I guess, that when I heard about a book, out this week, called (get this) Making Things—whose mission isn’t so much the accumulation of made things, but the elimination of extra stuff and consumerism—well, I was pretty sold from the jump.

I got in touch with its authors Erin Boyle and Rose Pearlman and we started to noodle on how to collaborate. For one, they’ll have a project in the upcoming May print issue of Treehouse (more on that, to come!). I also asked them to do something that I used to do in the magazine, which I personally always love to read: a co-interview in the style of Interview magazine. Always fun to listen to two heads chatting, yeah?

So, who are our heads?

Rose Pearlman is an artist, teacher, and textile designer, based in Brooklyn, NY. Rose's hooked rugs and other crafts have been wildly featured in magazines, galleries, and online; she also released a book through Roost Books, called Modern Rug Hooking, in 2019. Rose’s crafts, simply put, sort of rule—they’re always straightforward, functional, pretty, and generally use materials you might already have at your house.

Erin Boyle is a writer, also living in Brooklyn. She writes the very popular lifestyle blog Reading My Tea Leaves and a companion Substack called Tea Notes . Erin’s work focuses on living simply, tucked in the Venn Diagram between sustainability, consumerism, and family (read: aforementioned flow of stuff). Her first book, Simple Matters, came out in 2016 through Abrams.

We are so thrilled to have them! But, ok, enough of my yammering…

Erin: We started talking and decided to just hit record—keeping this extremely informal. We were talking about living with objects and what attracted me to Rose, and Rose to me. It was not a case of opposites attract.

Rose: That came later on (laughing).

E: We both share elements of our life online, so we first came across each other online. We had both gone to this exhibit that Maira Kalman had put on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was a recreation of her mother’s closet.

R: Sara Burman.

E: Sara Burman. It’s this incredible space of just ordinary objects.

R: Beautifully curated. And preserved and loved.

E: They were actually used items. And there was something about that that was compelling to both of us. Seeing that in each other it was like, ‘Oh you’re a person that I’m interested in.’

R: In all honesty, I was well aware of Erin before that. I was a fan of the blog. A fan of the book. I felt like she understood my aesthetic in terms of living in a small apartment, the things you want, the things you really don’t want to have on hand. A relationship to consumption and always just trying to find the thing that will work.

E: It’s access to things, too. We’re both creatives, our husbands are both teachers, we don’t live very fancy lives. We both live in rented apartments. There’s just some stuff we can’t afford or we can’t change about our homes. But, the objects in them we can control.

R: Yeah, it’s about control of the things surrounding you, but without feeling limited. Regardless of budget. Like, all the things we’re forced to live with, but still creating a home that you’re proud of.

E: And that feels particular to you.

R: Yes!

E: Even in our book, there’s so many different projects and different techniques, but very few supplies. I think that’s been the crux of it for us. How do you live this creative life, in limited space, with, honestly, relatively limited skills. I’m not an expert sewer, I’m not an expert knitter. I’m not really an expert in anything, but I feel like I have adopted this can-do attitude about it all.

R: We’re very scrappy in that sense. Where we are perfectionists, it’s not when it comes to crafting.

E: It’s interesting, we have very particular ideas about what we like, and yet we’re both pretty gentle with ourselves…

R: …about the final results. With the book, if we can make it…. I know that sounds ridiculous because I have this background in making rugs, which I do consider myself an expert in, but that comes after years and years. Even there, I teach, so I’m used to the beginner mindset. I really want to pare down the rug-making process to its most basic, without too much background information or advanced know-how.

E: That’s been interesting about our process. You develop these projects and then put them in my hands. And then I make it to your instructions… Neither of us are particularly good at following instructions, but we take it and run with it.

R: The interpretation, yeah. I come up with a lot of these projects, photograph the steps, write down a general sense of how to do it. Then, I put it into Erin’s hands and without being there, I see her follow the instructions. She would take photos along the way, and also the final product. She would synthesize the whole thing and write about it. And it was exactly the thing I was feeling in terms of materials and results and the uses for it. She would be able to perfectly organize what I wanted people to see, photograph it in a beautiful way. She was the perfect person to give these crafts to be so elevated.

E: I think it’s because we both have this reverence for the object itself. We have this real connectedness to this thing: it’s very functional and beautiful and I like it just the way it is. And so, we have this particular idea that’s aside from the consumption side of things. It’s really about practically.

R: Right, I mean, I don’t want to make anything that I don’t want to keep in my home. And so, process-driven is fantastic, but I need to see long term. I need to see how it’s going to be used. I want to see it around. I don’t want to have anything that’s just going to end up needing to be dusted.

If you see our homes, you see we are living and using these objects and they’re organizing our lives and they’re bringing us—at least, me, I don’t want to put words in your mouth—but so much pride. Knowing that I made them.

E: No, 100%. You develop a different relationship to things when you’re making them yourself.

R: And our relationship to consumption. Where I used to go, and shop in places, maybe not buy.

E: Window shop. Lust after things.

R: I don’t buy as much or want as much because I make it. The most value and satisfaction I get is when I can make an object, I think.

E: And the more you make things, you develop this material intelligence. You're able to go into a store and look at something and say, ‘I can see how that’s constructed and I can see the materials used. Let me see what materials I have and what skills I have that I can bring to bear to make my own version.’ Maybe.

R: And maybe you come out with something completely different.

E: Maybe it’s shit!

R: Maybe it’s shit… it’s not that we haven’t scrapped things.

E: We have definitely scrapped things. Not everything is going to be a winner.

R: And there’s a lot of room for interpretation. You can veer off. I don’t like anything that’s too prescriptive. I’m not a baker. I need to half pay attention to the instructions and go by the visual.

E: I kind of blur my eyes a little bit. And yet they still come out! Sometimes for the better. And then we make weirdo things, like a paper bag fly swatter.

R: It took a little convincing.

E: I was like ‘Who in the hell is going to make a paper bag fly swatter?’ But then you start making it and it’s so satisfying.

R: Did I send you the video of me killing a fly with it though? Just to prove? I was so proud when it actually, like, killed flies.

E: Gross.

R: You can just swap out the paper when it gets gross. You don’t have to bother trying to clean it.

E: Here’s the thing too: It doesn’t have to be a fly swatter. It can be a fan. It can be a trivet (for a not too hot thing). You can keep weaving it and form a basket. There are so many things you can do once you start to use your hands.

R: Exactly. That weaving technique translates to so many other things. Like the sit-upon.

E: Oh my god, I love the sit-upon.

R: Talk about a fail. You were like 'Can you make this out of newsprint?’ and then you have a newsprint tush.

E: It was very cool… but a little impractical.

R: It didn’t really pad that concrete step.

E: But it looked amazing.

R: It did look good. And then I tried to take it one step further and with canvas and, yeah, it was just a fail.

E: Kind of. But now that we’re even talking about it, I’m like, I don’t know. I bet it wouldn’t be a fail if we tried it again.

R: And, I don’t think I’d have the fly swatter if I didn’t have the sit-upon.

E: Totally.

R: So it all ~weaves~ into each other.

E: It’s generative. That’s what I keep coming back to. We’ve been talking a lot about the time we spend on social media and time spent that detracts from our lived life. The stuff in this book adds to it and the projects add upon each other. Like, each craft translates into another craft, that builds on a skill, that uses a material in a new way. It generates new ideas. It’s very rich in that—the more you make, the more you can make. The more you know how to make.

Just, go make something.

Edited for syntax and space!

Maine’s Marketplace cadence continues to be the best of all. “I no longer have use for them.” I’ll say. (LINK)

Free! (LINK)

Everything is fine. (LINK)

Wonder if this haunted Winnie is still available…? (LINK)

Oh joy! Thank you!

Thank you, thank you Zinzi! (So excited for the zine!!)